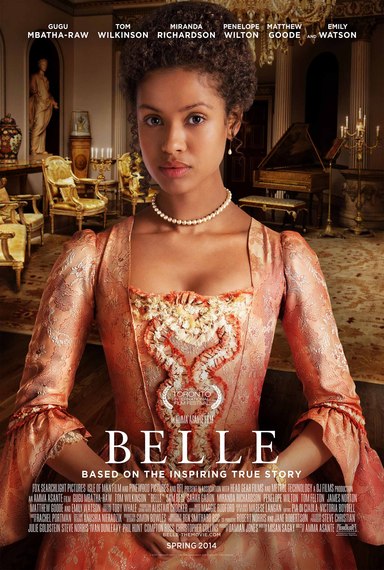

The Huffington Post: Amma Asante’s Belle May Lead to Real Freedom for Women Around the World

Posted on The Huffington Post:

What is especially intriguing about this film is that it is not atypical of films that have dared to tackle slavery. Conceived on a Spanish slave ship, Dido, the biracial daughter of Maria Belle, a black female slave, and Royal Navy Admiral John Lindsay, Dido was a slave. However, in Belle, the images of Dido are the very antithesis of the images of female slaves audiences have become accustomed to seeing film.

Dido’s life is quite unlike 12 Years A Slave’s Patsey, Django Unchained’s Broomhilda “Hildi” Von Shaft, Kizzy in Roots or Jane as depicted in the film adaptation of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman.

Moreover, Dido was neither ignored or rejected by her white father. He claimed her as his own and gave her his last name. He loved her so much that before returning to seamanship in the West Indies, he asked his Great Uncle, the revered and renowned Lord Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice of England and his wife, Lady Mansfield, to raise Dido at Kenwood House, their very grand country home.

Dido was raised as an aristocratic lady, side-by-side and equal in all respects to her white half-cousin, Elizabeth. She was mature beyond her years. She was cultured, well-read, multi-lingual, and extremely proficient in her delivery of British parliamentary styled tongue-lashings. She was an accomplished pianist and was clothed in spectacularly beautiful 18th century attire.

Ironically, in Belle, the death of Dido’s father leaves her, despite her blackness and femaleness, an heiress with the economic wherewithal to do, as society at that time expected all women to do – marry a man of the same or greater financial and social status. It is her white half-cousin Elizabeth who finds herself with few, if any prospects for a “proper” marriage because only a first-born male child could inherit a father’s estate. (Ironically, the United Kingdom didn’t pass gender-neutral succession laws until 2013). Elizabeth quickly and painfully discovers that a female’s prospect for marriage is more often than not purely about male financial gain. It is Elizabeth who must work hard to find a man who will marry a woman with no fortune, even if she is the niece of the highly regarded Lord Mansfield.

She may marry the man who loves and sees her as his equal – an abolitionist with no title or means, but with a fire in his heart to change the laws that support slavery.

She may marry the man who overcomes his prejudices and falls in love with her, but whose family would carry her race as their “shame.”

Or, secure in her wealth, she may remain unmarried, destined to take over the reins of caretaker of the family estate from her aging, never-married aunt.

As she comes into her own, Dido, declares, “I’ve come to realize I have freedom twice over, both as a Negro and as a woman. Or have I, for what is a woman if she doesn’t have a husband of consequence? It’s sort of like a free Negro begging for a master.”

Dido transforms from a girl who says, ‘As you wish sir,’ to a woman who says, ‘As I wish — this is what I need, this is what is important to me. She does so not because she is a privileged young woman who wants more, but because she is a woman saying, ‘I want equality in my household and in the world.

I will leave it to those of you who haven’t yet seen Belle to watch with breathless anticipation as Dido chooses her own path.

Asante’s Belle reminds us that women are as free by nature as the men we give life to. As Dido proclaims, “For all that you are, and with all that I am, I love you,” we are left hopeful that a love and respect for the inherent equality of all women will eventually lead to true freedom for women from India to China, to Nigeria to Syria, to Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran.

Just maybe, in some small way, Asante’s Belle will lead men the world over to recognize that equality and justice for all of humankind is the foundation of freedom, democracy and peace. We must remember that it was moral courage and a belief in the inherent equality of the Black Africans who were once sold into bondage as animals that led to the eventual abolition of slavery worldwide.

As Lord Mansfield tells us in in a poignant statement about the nature of freedom and morality that still resonates today, “Let justice be done though the heavens fall.”

Michelle D. Bernard is the president & CEO of the Bernard Center for Women, Politics & Public Policy and is the author of “Moving America Toward Justice: The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, 1963-2013″ and “Women’s Progress: How Women Are Wealthier, Healthier and More Independent Than Ever Before.” Follow her on Twitter @michellebernard.