Baraka Boys: Escaping Your Zip Code

Speaking before an enthusiastic audience at the Dorothy I. Height Community Academy Public Charter School on Wednesday, February 9, 2011, Michelle D. Bernard, president and CEO of the Bernard Center for Women, Politics & Public Policy said that too often in America, the quality of a child’s education “depends on one’s zip code.”

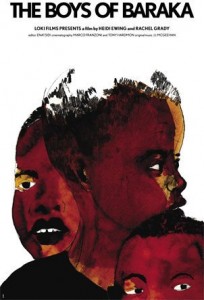

Bernard, who is determined to change that, was introducing a documentary about an educational experiment that took place in a zip code far away—the award-winning “The Boys of Baraka,” which follows four at-risk African-American boys in the seventh and eighth grades from troubled Baltimore schoolsthrough a year of boarding school in Kenya.Co-sponsor for last night’s screening and panel discussion was Kent Amos, a former Xerox executive who founded the Height school and is a well-known figure in the charter school movement.

The event was scheduled as part of National School Choice Week, but was held belatedly because of snow on the original date. Still it did not appear the delay had dampened anybody’s enthusiasm. A busload of young men—they introduce themselves as scholars—from the Bluford Drew Jemison S.T.E.M. Academy in Baltimore, Maryland, wearing striped ties and black blazers, had come for the evening. They joined dignitaries from the education field and students from Amos’s Height School in the audience, many donning yellow scarves bearing the National School Choice Week logo.

The film showed boys from troubled homes who were selected to attend the Baraka School as they learned to cope with their emotions and learn to study for the first time in Kenya. “The best thing about the Baraka School,” an administrator says on camera, “is that it lets these boys be boys, lets them be 13 and 14 year old kids without worrying about other things in their lives.” It is also the first time anybody has paid much attention to their academic development: one struggles to read on a second grade level.His reading problem simply had never been discovered in the public school system.

“You know what?” he says. “I am going to keep on trying to the day when I can’t try anymore,” he says.

The audience responded with knowing laughter to some of the boys’ experiences in Africa shown in the film but became deathly quiet when the parents of the boys were called together and informed that, because of political violence, the experiment would be discontinued—all the boys would be back in the public schools of Baltimore.The film shifts from the beautiful scenery in Kenya, where the boys climbed Mount Kenya, to the mean streets of Baltimore, where one former Baraka boy watches presumed drug dealers gather on a corner.

A 2002 evaluation done for the Baltimore school board indicated that boys who have participated in the Baraka program raised cumulative score on standard tests from 63.2 before to 84.2 afterward. One of the boys in the film, Devon Brown, whose mother was in prison while he was in the Baraka School, is a student at the Maryland Institute of Art, studying film, while another, Romesh Mustafa Vance, was indicted last year on drug charges.

After the screening, Bernard moderated a panel that included Amos,Imam Earl El-Amin from Baltimore and Tyron Young, who attended the Baraka School and is now an education major at Morehouse College, one of the nation’s historic all-black schools, in Atlanta, Ga.Bernard called Tyron “a member of that endangered species we call the black male teacher” and asked him to speak first. Tyron had to catch a plane immediately after the event and be back for a 7:30 a.m. class at Morehouse this morning!

The students in the audience were invited to question Young and did so enthusiastically. Young admitted that he was determined to do well even before going to the Baraka School but said that Baraka had made an enormous difference in his life. He has had more opportunity as a result and has learned more about making connections with other people.“Having had a choice about my education,” he said, “and having had better resources than I would have had in my public school was amazing. I can’t see why anyone would say that somebody else doesn’t have the right to go to a better school. We need more charter schools and we need more people to speak up for charter schools.”

Young was asked by a student if there were “bad influences” in Kenya, an apparent reference to unhealthy aspects of the Baraka boys’ lives once they returned to Baltimore. “Being in Kenya pulled me away from bad experiences,” he said. “You need to get involved in positive things. The bad influences will always be there, but you need to pull yourself away from them.”

After Young made his dash to catch his plane, Bernard turned her attention to Amos, noting that opponents of school choice often claim that it is unfair to the public schools because it takes kids out of under-performing schools, ultimately harming the very schools that some argue need the most support.

“What’s the argument against that?” Bernard asked.

Amos said that when the argument focuses on opt-out scholarships which allow money to go to parents to select private schools, “You’ll probably lose it.” He said that the better argument to make is that every child deserves a good education. Amos also stressed that schools must be realistic about the environments from which kids come and provide a sense of community. “The majority of our children are born to single families and we must acknowledge that that is the statistical reality today,” he said. But children still need men in their lives, he added.

“There is our police officer,” Amos said, recognizing a member of the audience. “He cares about the children in the school and comes out on a night like tonight. You have to find your men where they are. You have to find an officer or an accountant [to provide influence],” Amos said, provoking applause. “You need a team of people,” he added, “don’t try to do it on your own.”

One of the most touching aspects of the film was that some of the boys in it had contact with genuinely interested adults for the first time in their lives. Amos stressed that the importance of such attention can’t be overestimated, noting that all the children at the Height School are “my children.”

“There is a saying that water seeks its own level,” said the Imam El-Amin. “I tell young men to find people who have the same aspirations as you have and to become immune from bad influences. Find a mentor, those who have the same interests and stay with them.”He cited Rites of Passage, an acclaimed program he helped develop in Baltimore in the 1980s and 1990s, that helps young boys acquire the traits to become adult men.

Bernard closed the evening’s lively discussion by calling for more minority participation in the school choice movement. She noted that “the school choice movement outside D.C. is an overwhelmingly white movement. If you live in a rural area, if you are poor, if you are unemployed or underemployed, there is a good chance that your children do not have access to the best schools.It’s a matter of zip codes. School choice is the civil rights issue of today. People of color must reach out and explain what we mean by school choice and that as a nation, we have a moral obligation to make sure that every child has access to an excellent education.”

As people were preparing to leave, Bernard said to Amos that she’d been hearing him ask students, “What’s the word?” She wanted to know what that was all about, and Amos explained by asking the Height kids in the audience, “What’s the word?”

They replied with a resounding, “Excellence!”—the perfect note on which to end an evening that will undoubtedly become a milestone in the school choice movement in Washington, D.C.—and zip codes far away.

Charlotte Hays

Visiting Fellow, the Bernard Center for Women, Politics & Public Policy

February 10, 2011